On a recent trip to Berlin I happened to buy a couple of photo books. One was about Tina Modotti (1896-1942), whom I already knew vaguely, another about Edith Tudor-Hart (1908-1973) whom I frankly had never heard about before. The book was still wrapped in cellophane, so I could not take a look inside, but I decided to buy it based on the text on the back-cover alone.

Accidentally, Modotti and Tudor-Hart seem to have had a lot in common. They were both women, obviously, and not very far apart in age. They both lived most of their lives in exile or as immigrants. And they were both very much involved in the political struggles of their time, as communists and antifascists.

Modotti was born in Italy, but emigrated to USA with her family as a young girl. She became a model – and lover – of Edward Weston, with whom she travelled to Mexico in 1923. Here she evolved into a photographer in her own right. And while her relationship to Weston dried out, she became gradually involved in the social and political struggles taking place in Mexico. She made friends with activists and intellectuals of the left, such as the painter Diego Rivera, and joined the communist party.

Modotti was born in Italy, but emigrated to USA with her family as a young girl. She became a model – and lover – of Edward Weston, with whom she travelled to Mexico in 1923. Here she evolved into a photographer in her own right. And while her relationship to Weston dried out, she became gradually involved in the social and political struggles taking place in Mexico. She made friends with activists and intellectuals of the left, such as the painter Diego Rivera, and joined the communist party.

In 1929 her lover, an exiled Cuban revolutionary, is brutally assassinated, and the next year she is expelled from Mexico. Via Berlin and Moscow she goes to Paris, from where she carries out undercover missions in Europe on behalf of the International Red Aid. During the civil war she is in Spain, where she meets Robert Capa and Gerda Taro – but at that time, she has already given up her own career as a photographer.

In 1939 Modotti returns to Mexico. She socialises with artists in exile, such as Anna Seghers and Pablo Neruda, while her political activities becomes less intense. In 1942 she dies suddenly from a heart failure.

Tudor-Hart was born Edith Sushitzky. Her father was a secular Jew and social democrat, who ran a bookstore and publishing house in Vienna. As a young girl she worked in Montessori-kindergartens. She probably learned photography as part of her studies at the Bauhaus in 1930. It seems she was an organized communist from her youth. For that she was kept under observation by Special Branch when she visited London in 1930-31, and finally expelled from Britain for political reasons.

Back in Vienna she had some photographs published in the early 1930’s, but in 1933 she was arrested by the Dollfuss-regime while doing underground work for International Red Aid. However, she managed to escape from Austria and marry an Englishman, Alexander Tudor-Hart, whom she had met previously in London. This made her a British citizen, and for the rest of her life she lived in England. Her younger brother fled to England to, while her father took his own life as a reaction to the advance of fascism in Austria.

Tudor-Harts marriage didn’t last long. Meanwhile, she gave birth to a son, who suffered from autism. For the next 20 years or so, she worked as a freelance photographer for various magazines, made book illustrations, etc. She seems to have lived a modest life on a very low income. At the same time, however, she was involved in clandestine activities for the Soviet Union. There are some suggestions, that she was connected to the Cambridge spy ring. She is known to have destroyed many of her photographic notes and some negatives in 1951, when Kim Philby was taken into interrogation, probably out of fear that her home would be searched by the police.

Her last photo-essay was published in 1956, and she seems to have lived a quiet and unspectacular life until her death in 1973.

Modotti and Tudor-Hart both lived a life, which was from conventional. One must admire the courage, with which these women took their destiny in their own hands and confronted the great challenges of their time. They certainly paid a high price.

The works of these two remarkable women shares some common features, but are also clearly different. There is of course a social and political awareness among both, manifesting itself in choice of motifs: political manifestations, labour rallies and emphatic depictions of the daily life of the working class.

The works of these two remarkable women shares some common features, but are also clearly different. There is of course a social and political awareness among both, manifesting itself in choice of motifs: political manifestations, labour rallies and emphatic depictions of the daily life of the working class.

Among Modottis pictures, however, are also experiments with other types of motifs and with form. Her use of unusual viewpoints, diagonals and contrasts is clearly influenced by modernist photography. I would not be surprised, if she was inspired by a photographer like Rodschenko, even though there is no evidence of this. Some of her pictures can be seen here (not necessarily those in the book)

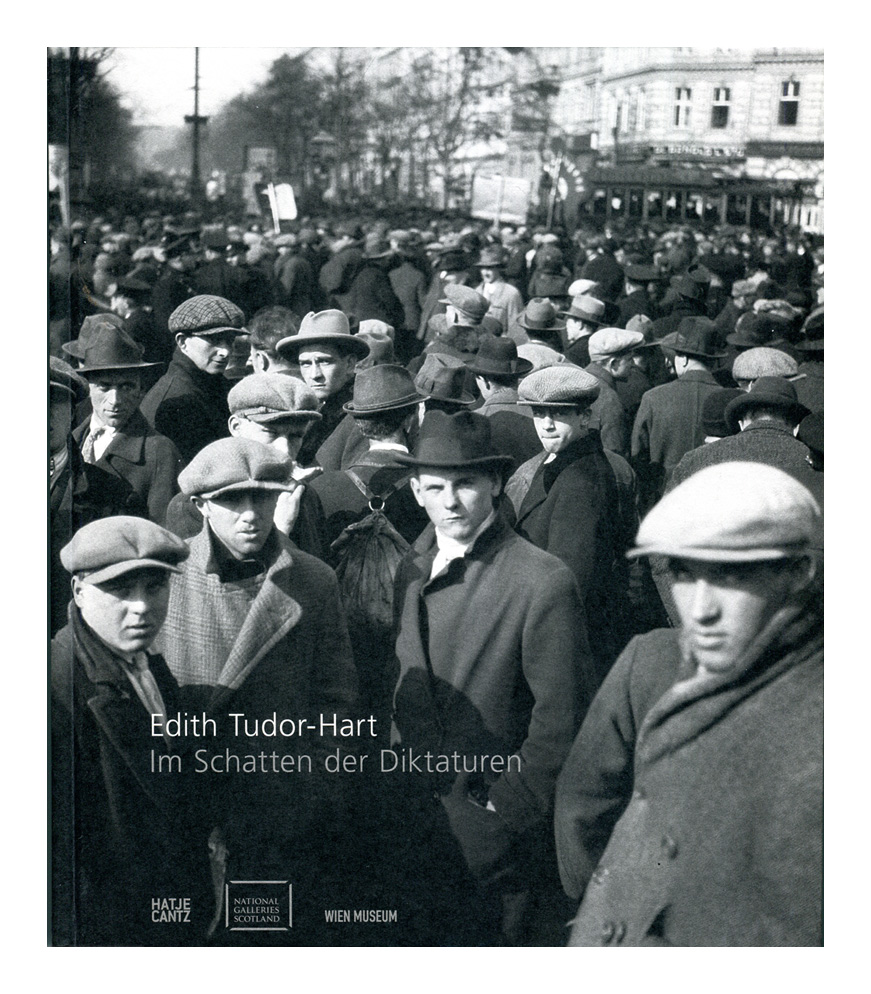

Tudor-Harts pictures are, with very few exceptions, not very experimental. Her best works are photo-essays and street photography, in which she captures the spirit and mood of the time and the people. She might be radical in her storytelling and humanism, as other central European photographers in this period, but not in form – despite her Bauhaus-experience. The book is also the catalogue for an exhibition, and som of the pictures can be seen here.

The two books are rather different. The one on Tudor-Hart is medium sized, with a great number of good quality prints. There is ample room to unfold her work, even in small series around the same theme, giving a good impression of her essayistic work. Many photos are reproduced from new ink-jet prints from her original negatives, but they look good. The week point is the text, which consists of five essays by three different authors. It is not that it is bad; on the contrary it is both learned an informative. But it is not very well structured, there are overlaps and missing points and the chronology is often unclear. It is also hard to use the book as a reference – an index would have helped a lot. But all in all, if you have just a slight interest in this type of photography, it’s worth the price.

The book on Modotti, on the other hand, is a bit smaller in size with significantly less pages – and consequently also fever prints. Some of the prints are rather small, but worse: most are in less than optimal quality. They have a rather low contrast appearance, sometimes with visible raster dots. The text is also shorter than in the Tudor-Hart book, but well written, well structured and to the point, and there is a good biographical overview at the end.

The Modotti book is clearly a labour of love from a small, dedicated publisher, and for that reason alone I would very much like to recommend it. But for the quality of the reproductions I hesitate. I have another book on Modotti from the Aperture Masters of Photography series, which features many of the same pictures in a better quality. But none of them are expensive, so you could always get both 🙂

Tina Modotti. Fotografien einer Revolutionärin.

Text (in German) by Christiane Barckhausen-Canale and Reinhard Schultz. 2012.

ISBN 978-3-939828-86-0, Hardcover, 21cm x 25cm, 96 pages, 19,90 €.

Verlag Wiljo Heinen

Edith Tudor Hart. Im Schatten der Diktaturen.

Text (in German, English edition available) by Duncan Forbes, Anton Holzer and Roberta McGrath. 2013.

ISBN 978-3-7757-3566-7, Hardcover, 25 cm x 29 cm, 127 pages, 35,00 €.

Hatje Cantz Verlag